Most days I feel like I’m drowning

I spend a lot of my free time wandering the outer edges of the barrier islands and rapidly eroding coastlines of the New York City metro

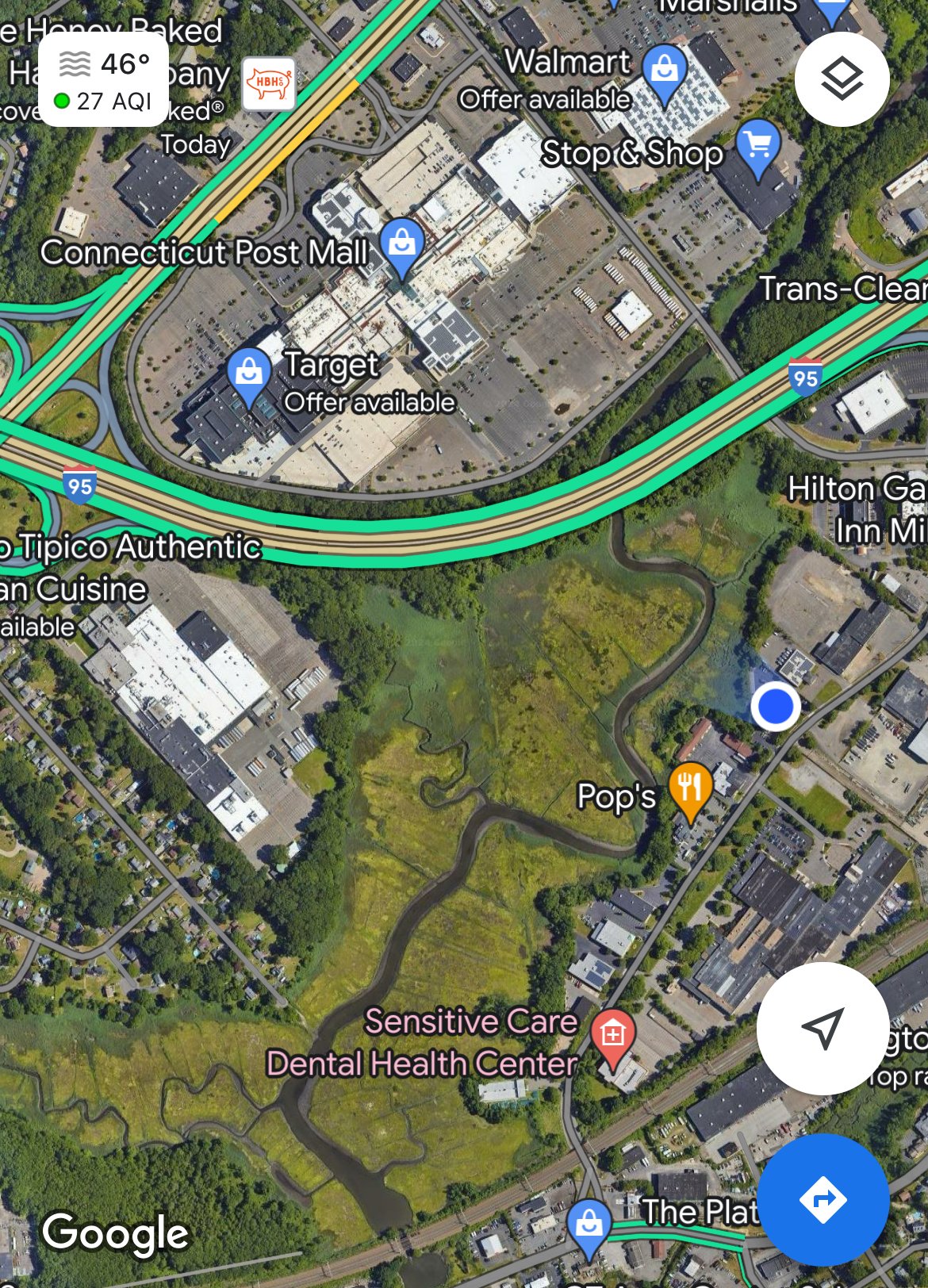

This morning I woke up to the rising light in a decaying hotel in Milford Connecticut. Since I’d rolled in late the night before, I shuffled over to my window to see where the hell I was and what I was looking at. Spread out before me stretched a fog-swept marsh, encircled by busy highways and shopping centers. The view could only be described as desolate.

As someone who lives in New York City but needs ~10 weekly hrs outdoors to remain sane, I’m no stranger to the sights and smells of the the Long Island Sound. Both its North and South shores are carved with infinite inlets, deep tidal bedforms, and bayside marshes that steal the shoes of the careless.

Tonight as I was getting ready to explore the edges of the estuarial basin outside my widow, I recognized myself as one of the careless ; when I reached for the marsh-logged boots I left “drying” in my backseat a week ago, I found them just as wet as I left them, smelling richly of the small ecosystem they’re now fostering within the sand-encrusted leather.

I spend a lot of my free time wandering the outer edges of the barrier islands and rapidly eroding coastlines of the New York City metro - most of which are teeming with litter, accessible only by car, and forcibly prevented from tidal and seasonal migration with various feats of coastal engineering. Last week I took my dog and the aforementioned boots to the very northern tip of Broad Channel, a landfill-buttressed island in the middle of Jamaica Bay that’s been bifurcated into a sprawling wildlife reserve and a tiny community of 3,000 people living perilously close to sea level who can politically best be described as … very very racist.

After parking at the foot of the Cross Bay Bridge, in a lot that’s technically reserved for canoe launches into the marshy archipelago, I traversed a long stretch of sand littered with Hindu devotional statues and wind-tangled ceremonial textiles. For the past several decades, outerborough Hindus have relied on this stretch of coastline for puja ceremony, a practice of making water offerings to Prithvi Maa to commemorate births, deaths, and marriages. The beach as a site of ceremony has drawn ire from the National Park Service since the early 70s, leading to the creation of numerous flyers and information campaigns targeting diasporic communities in Queens.

On the opposing end of the diety-strewn cove lies a tiny peninsula traversed only by the A train - a narrow spit of sand which is held in place by a breakwater made of 19th century headstones laid in a crooked assemblage that sort of resembles the charming jumble of the lower Manhattan grid.

A few of the sand-worn granite headstones still bear the names of the elsewhere-buried.

On the outer rim of the train peninsula I was surprised to find a windswept coastline bereft of graffiti, litter, or any evidence of recent human activity (aside from the hundreds of 150 year-old iron rail spikes, likely left over from the 1950s conversion of this spur from the steam powered Rockaway Railroad to the 3rd rail-powered IRT). Although I stood looking out at the misty outlines of JFK airport, and every 5-10 minutes a train to or from the Rockaways roared behind me, it felt like I’d been transported to the outer edges of Cape Cod.

When dusk started to fall over Jamaica Bay and the tide began to rise around my ankles, I made a steady retreat back to the parking lot. The gulls overhead commuted home to their home island further south in the falling light, and I sank wearily into the crevices between oyster beds, hollow phragmites stalks reverberating into the dark muck as they submerged deep into the mud along with my boots. As I finally neared my car, I watched a man dart out of a minivan bearing a red flag. He sprinted to the shoreline to proudly plant the pole in the wake of the waves, stood facing the wind with his hands on his hips, then spun on his heels to sprint back to the van.

I think a lot about marshland not only in the context as a place to rove around, and as a place for my own water ceremony, but also as a place of escape, of retreat, of disappearance. New York City was at one point the largest slave-holding colony in the North, with 40% of New York households in 1700 owning at least one slave. By 1712, 20% of New York City’s population was comprised of enslaved Black people - most of whom were born free in Kongo Kingdom, or Creole merchants and sailors who were European citizens trafficked to New York under threat of imprisonment for a falsified tax debt or a fabricated crime.

Remarkably, the scale of self-liberation and maroonage throughout the U.S. is often deeply - and perhaps intentionally - underreported and unmeasured. In New York State alone, tens of thousands of ads were taken out in local newspapers to track fugitive slaves through the twi-state area. The inclusion of these ads as evidence for mass scale self-liberation doesn’t even take into account the sheer number of people (often women, children, and disabled people) who were not considered valuable enough to buy a newspaper ad to track down.

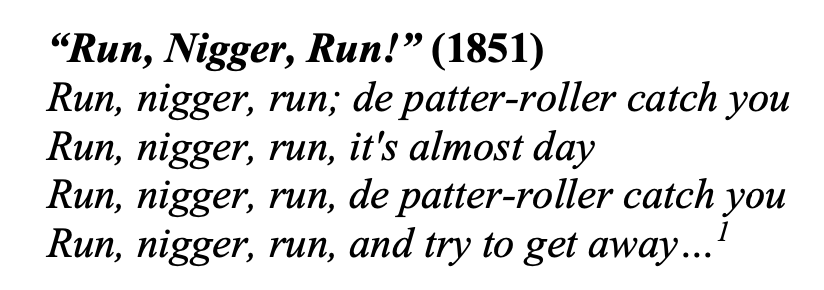

The memory around escaping slavery usually enshrines the abolitionist movement led by upper class white progressives ushering people along in a neatly orchestrated Underground Railroad. But how did people get from one place to another without being traced?

Self-proclaimed slave catchers, young white men and occasional Native mercenaries who tracked down humans on a for-hire basis, relied heavily on a local understanding of ecosystem, territory, weather, and social possibilities for free Black people in the region. However, the most advanced and eventually preeminent technology amongst slave catchers for tracking the escape paths of human beings was reliant on one thing - dogs. Dogs can track anything through any terrain better than any human, save for one - water.

Dogs can’t track a person across a body of water.

And this is where marshland comes in.

Throughout the New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut coastline that laps the Hudson and the Narrows and the Long Island Sound lie countless deep crevices of marsh, swamp, and tidal inlet. These soggy basins through which, if crossed at the right time under the right moon, with shoes and supplies held safely over your head as your bare feet sink deeper and deeper into cold salty lagoon, can shake the smell trail of a dog. You don’t need to know how to swim to traverse a marsh, nor do you need a boat - all you need to do is go slow. Be patient. Hold the silence. Don’t lose your shoe.

Earlier tonight - around 1 am, when the streets in Milford had emptied enough for me to duck unnoticed onto an unmarked but well-worn trail abutting an overpass - I ventured into the great sprawling estuary that I saw this morning. The recent rains had soaked the leaves below my feet, rendering my journey to the waterline silent save for the whine of wet truck tires on the highway. I crept over soggy mattresses and waterlogged underbrush to follow the dark trail as it hugged the back fences of bodyshops and other roadside hotels.

The tide was high, and the outer tendrils of still water sparkled around the base of the thick field of reeds that stretched out as far as I could see from the tide line. I stood and watched the stalks in their stillness, realizing after a while that I was waiting for any other living being to appear in my sightline - a startled deer, a sleeping fuck, another lone smoker roving up the trail, or maybe even the earliest & tiniest cries of a very very early spring frog.

But all i got back was silence. Stillness punctured by the trucks howling overhead.

*********************************************

Earlier this evening I’d googled this particular marshland, certain that there was someone stewarding this tiny patch of runoff in the heart of all creation - a rare slice of life located mere miles from Yale! One of the most well-funded research institutions on planet earth. What I found was a circa-1999 homepage for something called The Milford Institute, a hyperlocal community nature center that doubles as a small children’s science museum. There were very few photos available (the website kept imploring me to upgrade my Flash plugin), but the pictures I could see documented the Institute’s Archaeology summer camp - in which grade school-aged children spend full workdays unearthing Paugusset artifacts from the shores of the marsh. Under the tagline “Everybody participates”, the website proclaims that campers “create a Native name for themselves and learn to drum.”

In one grainy photo, a small white boy grimly holds up a granite hatchet head.

“The discovery of a full-grooved ax was the most important event of the 2011 camp season. The ax is estimated to between and (sic) 6 thousand years old.”

From the photo, I knew the smell of his ruined shoes.

I sat silently at the water’s edge wondering how many people are still submerged under the flow of the tides. I wonder, when their skulls and tools and memories churn above the water, if anyone will try to reach their relatives. The overcast sky bathed the fecund landscape in reflected red light from the ever-illuminated Pilot Gas marquis.

I can escape, I think to myself.

One night. Maybe I can escape.

Hopefully I’ll know which way to go.